Charles Dailey: How a Sierra College Biology Professor Procured a Gray Whale Skeleton

In the Spring of 1985 a student dropped off a newspaper clipping on zoology instructor Charles Dailey’s desk in Sewell Hall. It was about a fisherman’s find of a dead gray whale bobbing up and down under a pier at Benicia, just upstream of the Carquinez Straits Bridge. It had probably come into the bay to feed on shrimp. Dailey called the National Marine Fisheries Office in San Diego, which manages rare and endangered marine mammals. They had received numerous requests for various parts of the whale. Dailey asked if anyone had been crazy enough to request the entire whale. No one had…, yet! So Dailey did. They hadn’t decided what the fate would be but took his phone promised to call back with a decision. The next week a call came asking if he still wanted the entire whale body. He did. They had decided that if someone from their office came up and took possession of the whale and distributed parts that person would also be responsible for the disposal of all the rest of the whale. Soon the authorizing paperwork arrived.

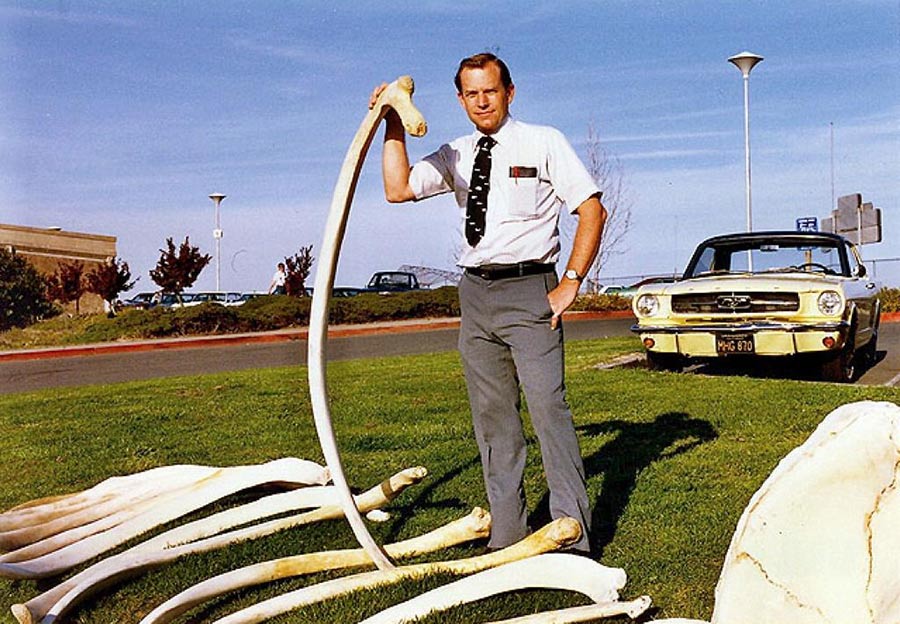

In the meantime, Dailey had bought some butcher knives, a machete, borrowed his dad’s chainsaw and a real whale flensing knife from the California Academy of Sciences.

The Marine Fisheries staff arranged with the Mare Island Naval Ship Yard to have an amphibious land craft tow “Bob” to the Napa County landfill. Dailey thought about renaming it “Skip.” At the dump, the tow rope got caught in the propellor shaft. One of the sailors had to jump in and untangle the rope. The rope was hooked to the dump’s dozer and it was dragged up onto the beach and renamed “Sandy.”

By now the whale had been dead going on two weeks. In the meantime, the baleen plates on the roof of the mouth had loosened and fallen to the bottom of the bay. Academy staff had warned about opening a long dead whale. One being towed on a trail through town in Japan explored from internal gasses. Someone who cut open the abdominal cavity of another one was covered in stinky whale guts and juices. Dailey took a rifle and reduced internal pressure before they opened it. The college’s small flatbed truck had been borrowed to bring the front flippers home on day one—Friday.

The next day the truck was used as a photography platform for the Special Olympics at the college athletic fields. The odor of the dead whale emanating from the wood deck boards all day long was memorable for the unfortunate photographer and bystanders. The next day Jim Wilson brought down a van full of Sierra biology students to help peel off the still two-to-six inch thick blubber and render the whale into chunks of skeleton. It hadn’t starved to death. The cause of death was not apparent. Dailey bought his dad’s dump truck on Saturday to hold the pieces of the skeleton and haul it back to the college. Memorable odor! Motorists passed holding their noses. On the way back, the truck scale operator at Vallejo just waived the dump truck on without asking for it to be stopped and weighed.

At the college there wasn’t any convenient place to store a long dead stinky whale. It went home to Charles’ place and sat in the truck for a few days. It’s new name was “Buzz” for the horde of flies swarming around. Dad needed the dump truck so “Phil” for unloaded into a hole dug with a backhoe. Three days later the downstream neighbors called asking about a horrible stench with nothing to explain it on their side of the creek. Soon Phil got covered with dirt and renamed “Barry.” A few weeks later Barry was renamed “Doug” and moved to near the sprinklers in the pasture to wash off the dirt, oils, etc. That helped, but six 50-gallon barrels worked better to leach out the light oils. The heavy oils and grease didn’t respond so the barrels were emptied, raised up on bricks, refilled, and fire built under each barrel. This did a much better job of extracting oils and grease from “Stu.” The last step was to take it to the automotive department and steam clean it. That really got the grease heated up and coming out, right down the cold drain pipe where it cooled and congealed and plugged up the drain pipe. OOPS! Chevron Oil Company donated $1,000 for supplies for final skeleton preparation and mounting. To prevent future odor problems, the bones were dipped in a solution of liquid plastic (polyvinyl chloride.)

Soon Dailey got college permission to drill holes in the concrete floor of the planetarium level to install cast bolts and cables to suspend the 1,200 pound whale skeleton. Installation was finished about 15 minutes before the opening of the college’s 50th Anniversary open house in 1986, 11 months total time. One of the next visitors to museum looked up and asked, “Where did you get the dinosaur?”

One of the more notable characteristics of the whale is his broken 9th right rib that never healed. It probably contributed to the bony deposits that fused two thoracic vertebrae and generated massive bony deposits on five of the lumbar vertebrae, the power area of the torso. They impinged on the nerve cord to the point that it probably either experienced excruciating pain when swimming or was paralyzed and drowned. The unusual bone growths look somewhat like rheumatoid arthritis, but are probably a result of the high calcium diet. It was a 38-foot-long, sexually mature male whale, but most of the vertebrae have unfused growth plates. If it had lived longer, it might have grown another foot or two before the growth plates fused. The pelvic bones do not attach to the spine. These are vestiges of their inheritance from ancient terrestrial ancestors. The posterior caudal vertebrae taper down to a tiny terminal version. The skeleton seems to be missing the tail flukes, but they were only fibrous cartilage, somewhat like huge versions of your ear flaps or nasal cartilage.

A few years later, a science center in the south bay area salvaged both sets of whale baleen (fingernail-like) fringed plates from a slightly smaller grey whale. They donated the right side to us, and we had it freeze dried. It is now installed so visitors can see how grey whales and scoop up mouths full of ocean bottom mud. They then inflate their tongues with blood to squirt the water and mud out between the plates, retaining the shrimp, crab, shellfish, etc. So now hanging for display we have Sierra College’s Gray Whale, “Art.”